Abraham Lincoln's White House

Copyright © Spring 2009 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

Peter Rothermel's The Republican Court in the Days of Lincoln, oil on canvas, painted in c.1867 to recall the ebullient spirit of Union in the recent Civil War.

On a hot summer day in August 1864, Abraham Lincoln strolled from his Second-Floor office to the lawn outside the Executive Mansion to greet a regiment of Ohio soldiers en route home after surviving some of the bloodiest fighting of the Civil War. Thanking the men profusely for their bravery and sacrifice, Lincoln implored the veterans to remember that the nation remained "an inestimable jewel" well "worth fighting for," not just for their own generation, but to guarantee "equal privileges" for "our children's children" as well. As he put it: "I happen temporarily to occupy this big White House. I am a living witness that any one of your children may look to come here as my father's child has."1 By the time he spoke these heartfelt words, it might be fair to say, Lincoln had endured nearly as much suffering and heartache in that "big White House" as the soldiers had on the battlefield.

However much the Lincolns—particularly Mary Lincoln—may have hoped for a glorious four years of social triumph and renewed intimacy at the nation's most famous residence, rebellion, civil war, and family tragedy conspired to puncture their dream. Although Mary dutifully hosted her share of public and diplomatic receptions, her husband grew increasingly occupied with running the government and the war, and before long the couple found themselves spending fewer hours together than at any time since his circuit-riding days as an attorney.

Mary's fond hopes for a palatial new existence in Washington were in a way dashed almost as soon as she took up residence in March 1861. As Lincoln's clerk William O. Stoddard conceded, many once glittering areas of the house were run down; even the East Room had "a faded, worn, untidy look."2 Mary's visiting cousin Lizzie Grimsley thought the "deplorably shabby furnishings" looked like they had "survived many Presidents," although the house had been extensively refurbished twice in the previous decade. Concluding that it would be "a degradation" to subject her family and her guests—to such surroundings, the new first lady launched a monumental redecorating project, purchasing new carpets, draperies, wallpaper, furnishings, china, and books, and modernizing plumbing, heating, and lighting.3

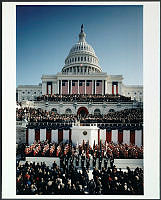

North Front of the White House at the time of Lincoln's inauguration. Iron fences and railings control public access to the grounds. The graveled walk, set in a flat-rolled lawn, encircles the Pierre Jean David dAngers statue of Thomas Jefferson, placed there by President James K. Polk in 1847 and since 1874 in Statuary Hall in the Capitol. To the right of the house barely can be seen the Conservatory, which was built atop the west terrace in the later 1850s and was filled with tubbed camellias and fruit trees.

No doubt much of this renovation initiative was sorely needed, but when Mary overran a generous congressional appropriation allocated for the effort—by nearly 30 percent—Lincoln swore to the commissioner of public buildings in December 1861 that he would never approve the bills for flub dubs for that damned old house!" As Lincoln viewed matters, it was "furnished well enough when they came better than any house they had ever lived in—& rather than put his name on such a bill he would pay it out of his own pocket." As the weary commander in chief declared: "It would stink in the land to have it said that an appropriation for $20,000 for furnishing the house had been overrun by the President when the poor freezing soldiers could not have blankets." 4

Eventually, the overrun was hushed up and made good—Lincoln was not required to make up the difference "out of his own pocket" after all, and Congress quietly supplemented the appropriation the following year—but the episode revealed the strains that White House life had already exacted on the president's marriage after only nine months in the mansion. Mary would not even tell her husband directly that she had overspent on its decor; she compelled the hapless commissioner of public buildings to bring him the bad news, and bear the brunt of his outrage.

The Lincoln Family, oil on canvas, 1865, by Francis Bicknell Carpenter, was widely published as an engraving and hung in many an American parlor through the balance of the nineteenth century. If it was posed, the sittings probably took place in the Soldiers Home. From left to right, Mrs. Lincoln, Willie (whom Carpenter added, for Willie died in 1862), Bob, Tad, and the president.

One aspect of White House life that made family life particularly difficult for the Lincolns was the mansion's open-door policy to the public, war notwithstanding. Virtually from Lincoln's first day in office, a crush of visitors besieged the White House stairways and corridors, climbed through windows at levees, and camped outside Lincoln's office door "on all conceivable errands, for all imaginable purposes." 5 Neither custom nor security precautions shielded the president from his voraciously demanding public. Office-seekers were the biggest drain on the presidents time and energy—among them, his wife's own relatives—crowding the hallways all the way down the front stairs in an endless effort to importune him for lucrative government appointments. As the first Republican president, Lincoln was expected by his party to cleanse the bureaucracy of Democratic holdovers, and when he failed to do so by the time of his inauguration, job aspirants made their way to Washington in quest of the loaves and fishes they believed theirs by right.

At first, Lincoln rejected his staffs efforts to spare him by limiting public access. "For myself," he insisted, "I feel—though the tax on my time is heavy—that no hours of my day are better employed than those which thus bring me again within the direct contact and atmosphere of the average of our whole people." 6 Eventually, however, the crush proved too much even for the generous Lincoln to bear, and his staff secured some concessions and organized a formal schedule.

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper of April 6, 1861, included this illustration along with a scathing article about the office-seekers who gathered outside Lincoln's meeting rooms and aggressively sought employment.

The original, daylong " promiscuous receptions," as Lincoln had taken to calling them, were thenceforth limited to twice weekly, for five hours each session, from 10 a.m. until 3 p.m. When even this arrangement proved too burdensome, the public hours were cut back to "only" three hours per session. Under the revised system, Lincoln joked, every applicant had to take his turn "as if waiting to be shaved at a barber's shop." But even with a truncated schedule, each open house, Lincoln continued to maintain, served "to renew in me a clearer and more vivid image of that great popular assemblage out of which I sprung. I tell you," he lectured one visitor, "that I call these receptions my 'public opinion baths," and their effect was for him "renovating and invigorating." 7 At least that is what he said publicly. To his assistant secretary Edward Duffield Neill, who was often required to referee the onslaught of callers, Lincoln "playfully" admitted that the crush reminded him more of a "Beggars Opera." 8

The White House architecture did little at first to protect Lincoln. In fact, only when he found himself unable to navigate between his office and the family parlor unmolested did White House maintenance men erect a partition that finally divided public and private spheres and allowed him at least to retreat for meals without running the gauntlet of assembled strangers. Those who were prevented from seeing him left stacks of letters, petitions, and pleas—and in some cases, inventions for his inspection. Clerk William O. Stoddard testified that so many newfangled weapons were deposited in the White House office that it came to resemble "a gunshop." 9

A hand-colored wood engraving from Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper captures President Lincoln welcoming guests to a New Years reception at the White House on January 1, 1862.

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (WHITE HOUSE COLLECTION )For a year, at least, the White House rang with the laughter of the Lincolns two energetic young sons (the eldest was off at college). Eleven-year-old Willie and eight-year-old Tad explored the vast mansion and merrily conducted such mischief as playing havoc with its intricate bell system for summoning servants, galloping a pet goat down the central corridor, and cutting up tablecloths to shreds with pocket knives. 10 To all of this, Lincoln turned a blind eye. A White House clerk observed Willie and Tad repeatedly burst into his office and interrupted meetings with "grave statesmen and pompous generals" but maintained that their company was "of more value to their father and to his work than anybody knew." 11

The White House was always more to the Lincolns than a family home, of course. It simultaneously served as a seven-days-per-week presidential office, a military hub, a magnet for tourists and favor-seekers, and at times, even a funeral chapel. When the Lincoln's young family friend, Colonel Ephraim Elmer Ellsworth, became the first officer killed in the Civil War in May 1861, a teary-eyed president ordered his body brought back to the White House for a state funeral, at which Mary placed the slain hero's photograph and a wreath on his casket. 12 A few months later, Lincoln ordered the mansion draped in black once again to mourn the death of his old political rival, and Mary's onetime admirer, Stephen A. Douglas. 13

In many ways, just as the president had declared, the White House was far better than any place the Lincolns ever lived in. Its family quarters boasted indoor plumbing (a luxury their Springfield, Illinois, home lacked), gas-fed lighting, separate bedrooms for the children, and a handsome suite and dressing chamber for Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln. The family no longer needed a kitchen, as meals were cooked and served from the White House galley below. Though the Lincolns Springfield residence had two small parlors and a tiny dining room and the private quarters upstairs at the White House provided only one common room—a combination library, dining area, and parlor—the Oval Room, as it was known, proved nearly as large as all three of the Lincoln homes rooms combined. Besides, the Lincolns were free to entertain small or large groups downstairs in the intimate Green, Blue, or Red Rooms, or hold levees in the vast East Room, the scene of many public receptions during their four years in residence.

This invitation to dine at the White House with the President and Mrs. Lincoln on February 4, 1863 is a traditional presidential engraved invitation blank filled out in ink.

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (WHITE HOUSE COLLECTION )

The wax seal that secured the envelope is impressed with the presidential seal and was not only an ornament but assured on delivery, if intact, that the invitation had not been opened en route from the White House.

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (WHITE HOUSE COLLECTION )For a time, the first lady appreciated the perquisites she now enjoyed. The living situation was "very different from home," Mary breathlessly observed soon after her arrival. "We only have to give our orders for the dinner, and dress in the proper season."14 The Lincolns now had several servants at their disposal, including doorkeeper Edward Moran, seamstress Rosetta Wells, cook Cornelia Mitchell, butler-waiter Peter Brown, and valet William Johnson, who traveled with the president to Gettysburg. 15 Helping the president with his day-today routine was a valet, and Mary was frequently attended by her seamstress, Elizabeth Keckly. The presidents two private secretaries, John George Nicolay and John M. Hay, lived in a room next to their outer office, constantly at Lincolns beck and call. It is little wonder that Mary wrote just a few weeks after moving in, "I am beginning to feel so perfectly at home, and enjoy everything so much." "Every evening," she marveled, "our blue room, is filled with the elite of the land." The "pleasure grounds" were "exquisite," she recalled, and the adjacent Conservatory "delightful," yielding "so many choice bouquets." A bit boastfully, she wrote that her visiting sister would probably never again be able to "settle down at home, since she has been here." Of her family, she added, "We may perhaps, at the close of four, years, be glad to relinquish our claims."16 But her joy proved brief, and not just because of the imbroglio over redecoration.

Their grand new situation did not automatically bring the Lincolns closer together, as Mary hoped; ultimately, it conspired in a sense to drive them farther apart. Although before his presidency Lincoln had never made his office in his home, his new proximity to his family did not guarantee them more shared time. Mary's cousin Lizzie, who remained in the White House for six full months after the inauguration, rationalized her delayed departure by explaining that the first lady "hates to be alone"—a strong indication that the busy president was growing increasingly unable to provide his wife the companionship she needed. The Lincolns eldest son, Robert, who spent his college vacations at the White House, later complained that once his father moved there, "any great intimacy between us became impossible. I scarcely even had ten minutes quiet talk with him during his Presidency, on account of his constant devotion to business." 17 To Robert, who decades later rejected appeals that he run for the presidency himself, living in the White House was like being confined to a "gilded prison." 18

The unfinished Washington Monument, seen to the right in a Civil War period photograph, was not the capital landmark that it is today. Simplified from the original 1836 design by Robert Mills, the Washington Monument was not to be totally completed inside and out for twenty-five more years, in 1888. In Lincolns presidency it remained the stub seen here, construction halted. Even had it been finished, it likely would have been eclipsed by the colossal new dome on the Capitol, completed during the war, that won Americans hearts as the symbol of Union.

Library of CongressThe cruelest blow to afflict the Lincolns during their time in the White House was undoubtedly the death of their beloved middle son, Willie, following an agonizing struggle with what is believed to have been typhoid fever. To make matters more difficult to bear, his decline followed on the heels of Marys greatest social triumph, an invitation-only ball that one Washington newspaper declared "a brilliant spectacle." 19 Two weeks later, on February 20, 1862, Willie succumbed, and his body was removed to the Green Room. Mary not only refused to attend the services for the boy; she never set foot in his White House bedroom again. "Our home is very beautiful," she acknowledged a few months later, still deep in mourning, in a desperately sad letter to a Springfield friend, "the grounds around us are enchanting, the world still smiles & pays homage, yet the charm is dispelled—everything appears a mockery." 20

Mary never recovered from the loss of her son. She found solace not at the White House, where she felt beset by critics and memories, but at the Soldiers Home, the summer presidential retreat north of town, and on occasional trips to New York or the White Mountains in Vermont. Social life at the mansion dwindled to such an extent that at one point Lincoln was compelled to ask that weekly Marine Band concerts be suspended because Mary could not bear the sound of music in the midst of her affliction.

Two weeks after Lincolns reelection in November 1864, even as Mary boasted with renewed energy that "the White House, has been quite a Mecca, of late," she confided her lonely White House isolation to her Springfield friend, Mercy Conkling: "I consider myself fortunate, if at eleven o'clock, I once more find myself, in my pleasant room & very especially, if my tired & weary Husband, is there, resting in the lounge to receive me—to chat over the occurrences of the day. 21

Lincoln also posed for artist Edward Dalton Marchant who spent nearly four months at the White House in 1863. The president is depicted seated beside a draped table, his arm resting on a document representing the Emancipation Proclamation.

COURTESY ABRAHAM LINCOLN FOUNDATION, UNION LEAGUE OF PHILADELPHIAThe crush of visitors was not the only "occurrence of the day" to require Lincolns constant time and attention. His daily work routine at the White House was crowded with military conferences, political meetings, speechwriting, and cabinet sessions, all of which took place in his bustling Second Floor corner office, its view of the ugly, unfinished Washington Monument a constant reminder of the fickle nature of public gratitude. Here Lincoln also attended to his vast and growing correspondence with the help of his clerks. Oddly, and inexplicably, the White House was never equipped with a telegraph system during Lincolns occupancy. For the latest news from the front—which he required often—the president had to walk across the West Yard to the War Department, where he spent many long and anguished nights waiting for news from the battlefield.

Not that his office lacked for historic events. Here, at his cabinet table, in what is now the Lincoln Bedroom, immediately following a long and exhausting New Years Day reception on January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, surely the most history-altering document ever promulgated in this house. And here, Lincoln inaugurated what years later became a routine White House occurrence—the photo opportunity. On April 26, 1864, at the request of painter Francis B. Carpenter, Lincoln posed in his office for Mathew Brady cameraman Anthony Berger. 22 It was one of the first times a president was ever photographed inside the White House, Polk having been the first in 1846. Lincoln also posed for a photographer on the mansions portico on March 6, 1865.

Lincoln sat here for painters and sculptors, too. Philadelphia artist Edward Dalton Marchant spent three months at the White House in 1863 creating a canvas of Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles hired Connecticut portrait painter Matthew Henry Wilson to depict Lincoln from life in February 1865. At around the same time, the precocious teen-age sculptor Vinnie Ream enjoyed several sittings with Lincoln on the way to producing the bust portrait she later adapted into the full-length statue now gracing the Capitol Rotunda.

Francis Bicknell Carpenters The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet was painted in oil at the White House in 1864. The artist used the State Dining Room for his studio studying firsthand every detail of the president's office and the individuals represented, to make his work accurate to history.

U.S. Senate CollectionPerhaps the most famous artistic project at Lincolns White House was the effort by New Yorker Carpenter, who arrived in February 1864 and spent the next six months working freely in the building to create his history painting of The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet— an event that had taken place in Lincolns office (or, some have maintained, the upstairs family parlor) in July 1862. Carpenter produced countless sketches during his sessions in the mansion, painted a model head of Lincoln, and then set up a 8 by 14 foot canvas inside the State Dining Room and there commenced painting the eight figures gathered around the cabinet table. Appropriately, Lincoln offered the East Room for the first public viewing of the finished work, where the president declared the work "perfectly satisfactory," to the artists delight. But when Mary Lincoln took her first look at the group portrait of her husband with the ministers with whom he had grown so close over the years—at her expense, she believed—she slyly dubbed it "The happy family." 23 Her comment spoke volumes.

The Lincolns "last best hope" 24 of making a new start in the White House ended almost as soon as it began. Only a month after Lincolns second inauguration, Robert E. Lees surrender at Appomattox at last brought the Civil War to an end. But less than a week later, on April 14, just hours after sharing a carriage ride during which they pledged to each other to be "more cheerful in the future," 25 the Lincolns drove off to see the play Our American Cousin at Fords Theatre. Mary returned to the White House the following morning a widow. She clung to the mansion for five weeks more, unable to summon the strength to leave and cede it to Andrew Johnson and his family until May 22, 1865, 26 and finally departing in "painful silence," Elizabeth Keckly remembered, "with scarcely a friend to tell her good-by." 27

"Bidding Adieu, to that house," she bitterly remembered, "would never have troubled me, if in my departure, I had carried with me, the loved ones, who entered the house, with me." Her memory of the White House was only that "all the sorrows of my life, occurred there." 28

The teenage sculptor Vinnie Ream was one of the several artists for whom Lincoln posed. She produced a bust that she later adapted into the full-length statue now in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Library of Congress