An Introduction to "Away From the White House"

Copyright © August 20, 2014 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

America's presidents have been trying to get away from it all for more than two hundred years and never quite succeeding. The job and its responsibilities follow no matter where they are. But vacationing presidents find that time away from the White House can clear the mind, rest the body, restore energy, and perhaps add a touch of humanity to a politician's image.

"This great white jail is a hell of a place in which to be alone," Harry Truman told his White House diary in 1947. When bleak winter set in, Truman broke free and flew south to the sun, palm trees, and evening poker awaiting him at Key West, Florida. "You can get a kind of a bird-in-a-gilded-cage feeling," Ronald Reagan told friends when he mused about White House life. Reagan escaped to his California ranch much more often than top aides thought wise. He made the continent-spanning trip on Air Force One not only to change scenery but to shed schedules and ceremony. At the ranch, the president rode horses, built fences, chopped wood, and cut brush.

During the summer of 1923, President Warren G. Harding greeted children in Valdez, Alaska, during his historic "Voyage of Understanding" his famous transcontinental speaking and sightseeing tour by railroad. Harding was the first president to visit Alaska.

White House Historical AssociationVacation was not a concept in anyone's mind when George Washington first stepped into his coach at the President's House in Philadelphia and headed to his Potomac River plantation. He and other early presidents went home to tend to private responsibilities at places with names: Mount Vernon, Peacefield, Monticello, Montpelier, and Oak Hill. It was an era when travel was measured by the speed of a coach and four horses pounding over rutted roads. For them and for many who followed, late summer in the capitals steamy heat served as a spur to explore cooler surroundings.

The great American vacation would not arrive until the middle of the nineteenth century, when the steamboat and the railroad increased the distances people could safely and comfortably travel. Then the telegraph made long-distance communication easier. The new technologies multiplied the options of presidents and ordinary Americans alike. An overnight steamer brought Andrew Jackson from Washington to the mouth of Chesapeake Bay for days of cold-water bathing. James K. Polk and later James Buchanan traveled by rail to their favorite spa to take the waters. Ulysses S. Grant spent summers in a cottage on the fashionable New Jersey Shore. The presidential yacht made its appearance, offering comfortable adventures on the river, bay, and ocean.

By the time the new century arrived, the nation's rail network offered new possibilities. A week or so on the train brought Rutherford B. Hayes, Chester A. Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt to Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Far West. Roosevelt could board a train in Washington and reach his home in Oyster Bay, New York, in less than a day. Once there, the telephone and telegraph kept him in touch with the White House, and the Atlantic and Pacific cables extended his reach around the world.

William Howard Taft motorized the White House, and greatly enjoyed whizzing down New England roads near his Summer White House while bundled in the backseat of an open touring car. The automobile also permitted visions of a permanent presidential retreat, secluded but located just a few hours drive from the White House. Herbert Hoover set the pattern with his fishing camp in the Blue Ridge, and Franklin D. Roosevelt established "Shangri-La" as a presidential hideout in the forests of western Maryland. Later, Dwight D. Eisenhower gave "Shangri-La" permanent status and a new name: Camp David.

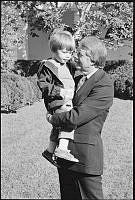

President Dwight D. Eisenhower's grandson David Eisenhower posed beneath his name on the sign at Camp David in 1960. According to Press Secretary Jim Haggerty, President Eisenhower renamed the retreat after his grandson and father, both named David, and David was his own middle name.

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home/ NARAOver two centuries the White House vacation has acquired the crust of controversy as opposition voices seek to dent a president's political armor by contending his vacations are untimely, too long, too expensive, and in the wrong place. The tactics first use may date from the summer of 1797 when an opposition newspaper in Philadelphia accused President John Adams of abandoning his post and going home just when the public most needed him at his desk and on the job.

Presidential escapes, retreats, and vacations away from the White House have changed a lot from the days when a president traveled with a few coachmen and outriders, a servant or two, and perhaps a private secretary. Today a vacationing president arrives at a vacation destination by U.S. Air Force jet, is transported by motorcade and helicopter, supported by communications staff, shielded by Secret Service and local police, and followed by a press corps intent on making the morning editions and the evening news. An urgent call can reach a president as easily on a golf cart, a sailboat, or a mountain path as it can in the Oval Office.

Presidential vacations continue despite hurdles and serial criticism. Contemporary presidents have discovered that frequent escapes offering absorbing activities and a break from the daily schedule can still rest the body, clear the mind, and renew energy for the work ahead.