Dwight D. Eisenhower

Bringing to the presidency his vast experience as commanding general of the victorious forces in Europe during World War II, Dwight Eisenhower oversaw the growth of postwar prosperity. In a rare boast he said, “The United States never lost a soldier or a foot of ground in my administration.... By God, it didn’t just happen—I’ll tell you that!”

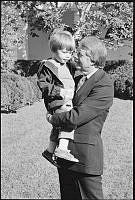

Born in Texas on October 14, 1890, brought up in Abilene, Kansas, Eisenhower was the third of seven sons. He excelled in sports in high school, and received an appointment to West Point. Stationed in Texas as a second lieutenant, he met Mamie Geneva Doud, whom he married in 1916. They had two sons, Doud Dwight, who died at two, and John.

In Eisenhower’s early army career, he excelled in staff assignments, serving under Generals John J. Pershing and Douglas MacArthur. After Pearl Harbor, General George C. Marshall called him to Washington to work on war plans. He commanded the Allied Forces landing in North Africa in November 1942; on D-Day, 1944, he was supreme commander of the troops invading France.

After the war, he became president of Columbia University, then took leave to assume supreme command over the new NATO forces being assembled in 1951. Republican emissaries to his headquarters near Paris persuaded him to run for president in 1952. “I like Ike” was an irresistible slogan; Eisenhower won a sweeping victory over Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson.

Negotiating from military strength, he tried to reduce the strains of the cold war. In 1953, the signing of a truce brought an armed peace along the border of South Korea. The death of Stalin the same year caused shifts in relations with the Soviet Union.

In Geneva in 1955, Eisenhower met with the leaders of the British, French, and Soviet governments. The president proposed that the United States and Soviet Union exchange blueprints of each other’s military establishments and “provide within our countries facilities for aerial photography to the other country.” But the Soviets vetoed his “Open Skies” proposal.

In September 1955, Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in Denver, Colorado. After seven weeks he left the hospital, and in February 1956 doctors told him he was well enough to seek a second term, which he won by another landslide over Stevenson.

In domestic policy the president pursued a middle “modern Republican” course, continuing most of the New Deal and Fair Deal programs and seeking a balanced budget. As desegregation of schools began, he sent troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, to assure compliance with the orders of the Supreme Court but resisted pleas from civil rights champions to welcome publicly the court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision.

During his last two years in office, Eisenhower tried to make “a chip in the granite” of the cold war. He welcomed Nikita Khrushchev to Camp David and planned to meet the Soviet leader at a four-power Paris summit the following spring to seek ways to reduce their antagonism. But just before the meeting, the Soviets shot down an American U-2 spy plane over their territory, which scuttled the summit and reinflamed cold war passions on both sides.

In his Farewell Address, Eisenhower surprised many Americans by warning them to “guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” which he found a potential danger to American liberties. Disappointed by his failure to turn over the presidency to a Republican successor, he and Mamie retired to their farm beside the Gettysburg battlefield. After years of cardiac illness, he died in Washington, D.C., on March 28, 1969.