Dumbwaiters in Place of Servants

Copyright © White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

When Thomas Jefferson entertained informally, he ordered five small serving stands to be placed at strategic points around the room. These "dumbwaiters" were small tables, equipped with shelves placed at varying heights. Some might hold salads and wine; others would accommodate cutlery and serving utensils. Servants brought in hot food, but did not remain in the room during the meal. Conversation could flow freely, without the possibility that workers might overhear sensitive information and repeat it outside the White House. 1

Margaret Bayard Smith visited both the White House and Jefferson's Virginia home, Monticello, during the first decade of the 19th century. She writes that the dumbwaiter "contained everything necessary for the progress of the dinner from beginning to end, so as to make the attendance of servants entirely unnecessary."2

Smith also describes an apparatus that Jefferson installed at both Monticello and in the White House:

"A set of shelves were so contrived in the wall, that on touching a spring they turned into the room loaded with the dishes placed on them by the servants, . . . and by the same process the removed dishes were conveyed out of the room."3

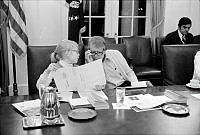

One of the two revolving serving devices at Adena, near Chillicothe, Ohio, built 1806-7. Benjamin Henry Latrobe planned this house for Senator Thomas Worthington, one of Thomas Jefferson’s frequent dinner guests. The senator may have based the design of these rotating shelves on those he admired at the President’s House.