Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Freemasonry and the White House

On July 16, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, formally the Act for Establishing the Temporary and Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States. The act empowered President George Washington and his three appointed commissioners to develop the country’s new capital and manage construction of the White House, United States Capitol, and other federal buildings. To meet their 1800 deadline, the commissioners hired dozens of stone masons, carpenters, bricklayers, sawyers, enslaved workers, and other skilled craftsmen from throughout the United States and abroad. When they arrived in the District of Columbia, a number of these craftsmen discovered that they shared an affiliation with the Freemasons, a fraternal society that traces its origins to eighteenth-century England. The fraternity soon entwined itself with the District’s early history and remained a fixture in Washington society and the White House for the next two centuries.

Origins

Freemasonry is the oldest fraternal society in the District of Columbia and models itself after the medieval guild system. Prospective candidates petition to join a lodge and are initiated into Freemasonry in three steps referred to as degrees. Each degree introduces a candidate to different moral and ethical lessons that are depicted through dramatic plays. Candidates are then taught the various signs, symbols, and secret modes of recognition for the respective degrees. They advance once they are found proficient in the preceding degree.1

The fraternity became popular in England and Scotland during the eighteenth century and spread into western Europe and the Americas. American lodges formed mostly in cosmopolitan areas like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia where they attracted men in the middle and upper classes who could afford initiation fees and annual dues. Notable early members included Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Paul Revere who joined lodges near their respective homes to improve their social standing. The fraternity’s values and principles, steeped in Enlightenment philosophy and liberal education, attracted many prospective candidates. Unlike their contemporaries, early lodges remained relatively small, composed of around twenty to thirty members, and membership fluctuated greatly due to business and travel demands. Members held their private meetings and social events in taverns, coffee houses, and other public spaces and later pooled their resources to build dedicated masonic halls. Lodges formed throughout the colonial United States and became early networks to connect traveling masons and provide business, lodging, or other forms of financial support.2

Lithograph of masonic symbols, 1876.

Library of CongressOn April 21, 1789, more than a year before Congress passed the Residence Act, a group of Georgetown merchants formed the town’s first lodge, which they called Lodge 9.3 Early records link some of the town’s most prominent men with the lodge including Charles Fierer, a printer and publisher of the District’s first newspaper The Times and Patowmack Packet; the Reverend Stephen “Bloomer” Balch, founder of the town’s first Presbyterian church; and John Suter, proprietor of Suter’s Tavern where the lodge held their meetings and social events.4

Construction

In July 1792, President Washington and the commissioners selected Irish architect James Hoban’s designs for the proposed President’s House. Hoban became a freemason in South Carolina but remained active after he relocated to Washington. With few laborers available in Georgetown and the vicinity, Hoban and the commissioners recruited skilled labor from throughout the United States and abroad. Of the approximate one hundred and fifty free and enslaved laborers who relocated to the District to build the White House, around twenty were known freemasons. This group included Pierce Purcell, Hoban’s business partner and supervisor of carpentry; Collen Williamson, superintendent of stone masonry; Clotworthy Stephenson, master carpenter; Bernard Crook, stone cutter foreman; Redmon Purcell, carpenter and joiner foreman; James Dougherty, stone cutter; and general laborers William Coghlan, David Cumming, and Andrew Eastave. Meanwhile, while on business in Edinburgh, Scotland, Philadelphia merchant George Walker secured seven more expert stone masons who had all been members of Lodge of the Journeymen 8.5

The commissioners arranged for Georgetown carpenter and Lodge 9 member William Knowles to build the homes, workshops, and sheds around the White House for the workers. These laborers worked six days a week, in ten-hour shifts, while under intense weather and travel conditions. Spartan living and working conditions meant that Hoban and company relied on themselves for entertainment. In lieu of attending Lodge 9’s evening meetings back in Georgetown, they decided to form their own lodge closer to the White House. They began to meet informally sometime in the spring or summer of 1793.6

Meanwhile, to help fund the White House’s construction, the commissioners placed notices in local and national newspapers advertising tracts of land for sale. In early fall of 1792, they arranged for Lodge 9 to lay the White House cornerstone in a public ceremony. They hoped the event would generate sales and raise funds to pay their workforce and secure supplies.7

The White House cornerstone ceremony occurred on October 13, 1792. Participants assembled at Suter’s Tavern in Georgetown and formed a long procession composed of the town’s mayor, town council, the District’s commissioners, Freemasons, and guests. They departed east and arrived in the open tract prepared for the ceremony. While the single known newspaper account does not specify who did what during the ceremony, Peter Casanave, the lodge’s leader referred to as the Master, and his assistants likely presided over the cornerstone ritual.8 A brass plate engraved with a special inscription was deposited under the stone. Workmen, perhaps Collen Williamson in his role as project superintendent, lowered the stone onto its final position. The inscription on the plate read:

This first Stone of the President’s House was laid the 13th Day of October, 1792,

and in the 17th Year of the Independence of the United States of America.

George Washington, President

Thomas Johnson, Doctor Stuart, Daniel Carroll, Commissioners

James Hoban, Architect

Collen Williamson, Master-Mason9

Vivat Republica.10

George Washington lays that U.S. Capitol cornerstone. Mural by Allyn Cox in the Capitol.

Architect of the CapitolCasanave likely poured vessels containing corn, wine, and oil on top of the stone and tapped the stone with a mallet or gavel three times to symbolically complete the exercises.11 Casanave and his assistants scaled back up the trench where he made a brief speech and returned to Suter’s for a celebratory dinner. Participants performed sixteen toasts dedicated to notable individuals and groups including George Washington, the French nation, Thomas Paine, and the Fair Daughters of America.12

The White House cornerstone ceremony became the earliest masonic event in Washington City.13 Although he did not attend the event, George Washington did participate in a similar ceremony for the U.S. Capitol the following year on September 18, 1793. Several days before the Capitol ceremony, Hoban and his colleagues obtained an official charter to become Federal Lodge 1 and made their first public appearance during the event.14 Freemasonry grew significantly during the 1800s as new masons arrived in Washington as part of the federal government’s relocation to the District. The District grew from two lodges in 1793 to five by 1810. The White House and Capitol cornerstone ceremonies became seminal moments in American masonic history and set a precedent for future interactions between the presidents and the local fraternity.15

Masonic Receptions at the White House

Presidents have hosted local and national masonic delegations since the White House’s completion. In April 1826, President John Quincy Adams met with National Intelligencer owner William W. Seaton and D.C. Mayor Roger C. Weightman, both Freemasons, who solicited Adams for a subscription to help build the fraternity’s new masonic temple in Washington.16 On January 4, 1830, Federal Lodge 1 elected President Andrew Jackson as an honorary member along with Secretary of War John Eaton and Postmaster General William T. Barry.17

President Andrew Johnson welcomed members of the Supreme Council, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, to the White House on April 23, 1867. The visit, composed of masonic leaders from across the United States of America, coincided with the body’s national conference in Washington. When the Supreme Council relocated their headquarters to Washington permanently in the summer of 1869, the organization made regular trips to the White House to visit presidents during their biennial sessions.18

On October 15, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant participated in the White House’s first inspection ceremony performed by the local Knights Templar.19 Knights adorned themselves with decorative plumbed hats, black frocks with military-inspired jewels, and carried ceremonial swords. The knights obtained Grant’s permission to assemble on the White House Ellipse and perform pseudo-military marches and drills. The event concluded with a final march onto the White House Grounds and a formal inspection by the president from the South Portico. Templar inspections became popular annual events up until the early 1930s and featured visiting delegations from New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts.20

Presidents Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley each held large masonic receptions at the White House during national masonic conventions. White House staff opened the building's State Floor so that visiting Masons could walk through and exhibit the mansion’s public rooms and parlors. Staff decorated the floor with masonic-themed floral arrangements and bunting. Thousands of masons and guests attended Harrison’s evening reception on October 9, 1889. The reception line grew so long that it wrapped around the block and extended several blocks past the State, War, and Navy Building. Seven thousand visitors greeted President McKinley during his reception for visiting Shriners on May 23, 1900. He “shook hands with the entire throng as it passed rapidly by him. It was thought that before the end of the evening he would probably be obliged to give up the handshaking for a bow, but he continued manfully to receive fifty guests a minute for three hours.”21

First ladies, including Florence Harding, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Bess Truman also performed formal hosting duties and arranged receptions and teas for visiting masons and their family during national conventions in Washington.22 Roosevelt also attend the fraternity’s Easter Sunrise Services at the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater from 1933 to 1945.23

Eleanor Roosevelt attends Knights Templar Easter Service at Arlington National Cemetery, 1937.

Library of CongressMasonic Initiations in the White House

In June 1867, Andrew Johnson became the first president to undergo a masonic initiation at the White House.24 His executive schedule prevented him from holding the ceremony at the masonic Temple on 9th and F Streets Northwest and the initiation moved to the White House. Benjamin B. French, former commissioner of public buildings and Grand Master of masons, presided over the initiation. French and his colleague Azariah T.C. Pierson arrived at the White House just before lunch.25 They dined with Johnson in the library on the Second Floor and then retired to his personal quarters where French and Pierson conferred the Scottish Rite degrees and instructed Johnson on the various signs, passwords, and lectures.26

President William H. Taft welcomed a delegation from the Mystic Order of Veiled Prophets of the Enchanted Realm, a masonic appendant organization, in 1911. They initiated Taft into the body during a private ceremony in the Oval Office. Similar ceremonies were held in the Oval Office for Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 by a delegation from the Tall Cedars of Lebanon and in 1977 for Gerald Ford by the D.C. Royal Arch and Cryptic Council bodies.27

President Taft wearing George Washington's masonic regalia during a photo session in the White House, 1911.

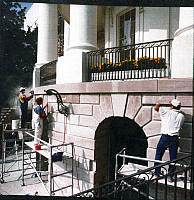

Library of CongressPublic Cornerstone Ceremonies

Since George Washington, many presidents have participated in public cornerstone laying ceremonies performed by the city’s Freemasons. On August 22, 1820, James Monroe attended the cornerstone ceremony of the District’s first City Hall - now the District’s Court of Appeals Building. President and Freemason James Polk attended two cornerstone ceremonies during his tenure in office for the Smithsonian Institution ceremony on May 1, 1847, and the Washington Monument on July 4, 1848. President Chester Arthur witnessed the masonic dedication services for the Washington Monument on February 21, 1885. President and Freemason Theodore Roosevelt performed his famous “Man with the Muckrake” speech following the masonic cornerstone ceremony for the new House of Representatives building on April 15, 1906.28 The following year, Roosevelt laid the cornerstone of the city’s new Masonic Temple on 13th Street, now the National Museum of Women in the Arts. On October 13, 1992, President George H. W. Bush welcomed masonic leaders from Washington, D.C., Virginia, and Maryland to the White House to participate in a special ceremony commemorating the White House cornerstone’s bicentennial. A time capsule was buried during the occasion.29

Truman Renovation Stones and the Original Cornerstone

The White House underwent a complete renovation during President Harry S. Truman’s second term. During the initial excavation, workmen discovered stones bearing markings believed to be made by the building’s first stone masons. Truman, an active Freemason and former Grand Master of Missouri, ordered that the stones be carefully extracted and preserved. In the fall of 1952, Truman invited D.C. Grand Master and city commissioner Renah Camalier to distribute the stones to each state Grand Lodge and several other national masonic organizations throughout the country. Each stone included a signed letter by President Truman, framed with wood taken from the White House, on the stone’s provenance.30

The renovation project spurred interest in the building's early history. A congressional committee tasked with managing the project partnered with local and national historians to compile as much information on the White House, which included any information on the original cornerstone ceremony. The search prompted the discovery of a newspaper article, first published in the Charleston Gazette, South Carolina, in November 1792, which turned out to be the only known eyewitness account of the cornerstone event. The account aligned with surviving masonic sources to confirm key moments and participants.31

White House renovation architect Lorenzo S. Winslow and his assistant Colonel Douglas H. Gillettee referred to the newspaper source during their own search for the cornerstone. Winslow and Gillettee posited that if the brass plaque deposited below the cornerstone during the first 1792 ceremony remained intact, it could be found using a metal detector - a relatively new technology at the time. They scanned the building’s walls, picked up a signal near the south-west corner, and relayed their potential discovery back to the commission’s executive secretary, Major General Glen H. Edgerton, and to President Harry S. Truman. Truman’s aides planned to extract and reinstall the plaque during another public ceremony despite objections by the Washington Post editorial board and R. Baker Harris, a prominent Washington mason and Librarian of the Scottish Rite’s House of the Temple. According to White House Curator Rex Scouten, who served on Truman’s Secret Service detail during the discovery, Truman did not wish to disturb the stone unnecessarily and scrapped the stone ceremony. The stone and plaque are believed to be still in their original location today despite another attempt to locate the stone during President George H. W. Bush’s term in office.32

Chris Ruli is a Washington, DC-based researcher, and historian on early American Freemasonry and the fraternity's role in local and national politics. He is the author of The White House & The Freemasons.