Presidential Valets

Confidantes of the Wardrobe

Copyright © Fall 2012 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

Perhaps no one knows the presidential wardrobe as intimately as the president’s valet.

John Hutton for White House Historical AssociationThroughout the history of the presidency, a president’s clothing choices have been influenced by a number of factors. Personal background, economics, regional influences, direction from the first lady, and advice from other family members and staff have all contributed to the sartorial style of the nation’s leader. Perhaps no one knew the presidential wardrobe, and the man himself, as intimately as the president’s valet. In addition to caring for the presidential clothing, valets were personal assistants, messengers, confidants, nurses, barbers, bartenders, waiters, public relations agents, and companions. Some were considered unofficial members of the first family.

Valets have always been a presence with the presidents. The earliest, George Washington’s William Lee, James Madison’s Paul Jennings, and John Tyler’s Armistead, were slaves. Nevertheless, the men were devoted confidantes of the presidents, and the loyalty was reciprocated. Lee was the only slave specifically freed in Washington’s will, and Jennings wrote a fond and historically important memoir of his years with James and Dolley Madison.1 When President Abraham Lincoln’s valet William Johnson died in January 1864, the president arranged for a burial at Arlington National Cemetery and paid for the headstone.2 Theodore Roosevelt became acquainted with a mounted Metropolitan Police escort, James Amos, during their horseback rides through Rock Creek Park and hired him, initially, to look after the younger Roosevelt children.3

Military service prepared several valets-to-be. Colonel Arthur Brooks commanded a National Guard unit during the Spanish-American War and went to the White House in 1909 from the War Department, where he had served Secretary William Howard Taft. Brooks remained at the White House until his death in 1924 after serving Presidents Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and Calvin Coolidge. Kosta Boris met Herbert Hoover in Paris in 1918 after he was assigned by the army to the U.S. Food Administrator’s Office. Master Sergeant John Moaney became a houseman for General Dwight Eisenhower in 1942, and the two men were together nearly every day until Eisenhower’s death twenty-seven years later.

Presidential valets witnessed the most private of moments of their boss’s lives. Irvin McDuffie, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s valet, was essential to the disabled president and in that way is unique among presidential valets. One of the duties of George Thomas, President John Kennedy’s valet, was to help JFK into the brace that eased his painful back, despite the fact that his chronic condition was played down to the public to maintain a youthful, robust image. Thomas also kept JFK’s clothes impeccable—no easy feat for a man known to change clothes three or four times a day. President Richard M. Nixon leaned heavily on Manolo Sanchez, a loyal and sympathetic sounding board, during his last two years in the White House. The pair even shared a unique system of communication, sometimes using words that only the two of them understood.4

Nixon was the last president to bring his own valet with him to the White House. Today’s presidential valets are specially selected members of the military assigned to the president or are regular members of the White House staff. Both new president and valet must adjust to the new relationship. Laura Bush recalled that President George W. Bush pulled his father aside after meeting his valets, Sam Sutton and Fidel Medina, to say, “I don’t think I need a valet.” “Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it,” replied the elder Bush.5

The following sketches profile three presidential valets of the mid-twentieth century: Kosta Boris, Irvin McDuffie, and John Moaney. Each enjoyed a shared esteem, deep sense of respect, and intimate personal knowledge of Presidents Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, and Eisenhower, respectively. Responsible for everything from the shine of the presidential shoe to the care of White House children and grandchildren, these men shared a unique role in White House history.

Kosta Boris

President Herbert Hoover's Valet

Kosta Boris was born in Ustice, Serbia, in 1889. Following his brother to the United States in 1907, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen and voluntarily joined the army during World War I. Fluent in French, Serbian, and English, he had language skills that led to his assignment to the United States Food Administration headquarters in Paris in 1918, where he served as an orderly to Administrator Herbert Hoover and other officials. “Whenever anyone needed anything and so forth, they would speak to me. I’d talk to the housekeeper and the butler and different ones about whatever needed to be done,” Boris said.6 When the time came for Hoover to return to the United States, he asked Boris if he would like to come to work for him as a valet. “I had many offers from other people, country club[s], etc.,” he recalled, “but I said, [to Hoover] yes, I want to go with you.”7

After World War I, Boris moved with the Hoovers and their sons to Palo Alto, California, where following years of living in exotic locales in Europe, England, Australia, and China, they planned to stay. In California, Boris’s duties involved primarily packing luggage for Hoover, who by no means settled down and whose travel increased along with his political profile. In the parents’ absence, Boris looked after the Hoovers’ sons, Herbert Jr., enrolled at Stanford, and Allan, a student at Palo Alto High School. The family became great friends with the tall Serbian, whom they teasingly referred to as “Factum Factotum” or “Domestic Maestro.”8 When Hoover joined President Harding’s cabinet as secretary of commerce in 1921, Boris accompanied him to Washington. “I went with him . . . and took care of Mr. Hoover— nothing else,” he said.9

With the Hoover family in California and the Hoover sons growing up, Boris’s duties evolved into those traditionally associated with a valet: serving meals, running errands, greeting guests, and maintaining the secretary’s wardrobe. In 1928, Hoover was elected president, and Boris (the traditional last-name address was used for male upper-level attendants) moved into to the White House, occupying a room near the president’s, according to Boris’s son Richard.10 Hoover, who had become a very wealthy man early in his career as an engineer, was a stickler for domestic correctness. He dressed in formal clothes for dinner every evening, even on the rare occasions that he dined alone. In a 1966 oral history with the Hoover Library, Boris described the president’s impeccable wardrobe and Mr. Gilbert, a Washington tailor preferred by the president:

"He had his full dress clothes in the White House, a tuxedo, a cutaway coat, two blue suits, one brown and, of course, pairs of white trousers, white shoes, blue coat; a Palm Beach suit. It had a little belt in the back. And I used to go to Mr. Gilbert at 17th and Pennsylvania Avenue and I would get some things there. Mr. Hoover would say, “Tell Mr. Gilbert I need a pair, two pair, or three pair of Trousers—white ones.” I would go to Mr. Gilbert and tell him what the Chief wants."11

Boris became a familiar presence in the Hoover White House, and his heavy accent and dark good looks made a memorable impression on both guests and staff. A White House seamstress, Lillian Rogers Parks, described him as “tall and handsome, with salt-and-pepper hair,” and said he “looked more like a diplomat than a valet.”12 An article in the New York Times stated he was “guardian of the children, handyman, factotum of the guests, an indispensable cog in the machinery of the household.”13 Not everyone was so taken with the valet. “Boris was just in everyone’s way,” said Chief Usher Irwin “Ike” Hoover.14

An errand for Mrs. Hoover led to his introduction to Essie Paul, a salesclerk in a downtown department store and his future wife. After their initial meeting she told her uncle, a newspaper columnist who attended White House press conferences, that she had waited on a “K. Boris” who worked at the Executive Mansion. He admitted that he was not familiar with the name, but after learning his identity, reported back, “That man you waited on is the closest man to the President of the United States.”15

After Hoover’s defeat for reelection in 1932, Boris returned to California with the Hoovers and worked for them until 1934, when the former president moved to New York, taking up residence in Manhattan’s Waldorf Astoria. Kosta and Essie, not wanting to leave California, remained in Palo Alto, where they joined the staff when the Hoover residence became the home of Stanford University’s president. Boris went on to serve two Stanford presidents before his retirement in 1968. He remained close to the former president, seeing him annually until Hoover’s death in 1964. Boris and his family traveled to West Branch, Iowa, for the funeral in a plane provided by the Hoover family.16 Kosta Boris died in Palo Alto in 1979 at the age of 89.

Irvin McDuffie

President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Valet

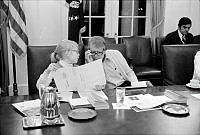

Irvin Henry McDuffie was born in Elberton, Georgia, in 1882. His formal education ended at the eighth grade, when he began shining shoes at a local barber shop. In 1900, he moved to Atlanta, where he met Elizabeth “Lizzie” Hall, whom he married in 1913. As he learned the barber trade, he took a valet position with the German consul in Atlanta and discovered that he enjoyed the work. By the early 1920s, McDuffie co-owned a successful Atlanta barbershop, but a 1927 injury to his legs left him unable to stand for long periods of time. A customer who supplied building material to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Warm Springs Foundation, south of Atlanta, overheard McDuffie expressing a desire to return to a valet position and mentioned the barber’s remark to FDR. A meeting was arranged, and McDuffie was hired after a ten-minute interview.17 Upon learning that McDuffie was concerned about what his wife would do when FDR returned to New York, the Roosevelts hired Lizzie as a maid.

When they arrived in New York, FDR launched himself into the governor’s race and the McDuffies got their first taste of life in the public eye. They also learned that, despite his handicap, Roosevelt’s energy seemed limitless. “He can work five men to death while he lies in bed,” McDuffie said of FDR.18

“Mac,” as FDR called him, fussed over Roosevelt’s health, chiding him to bundle up against the cold and pleading with him not to go outside immediately after a bath. “I don’t know what I would have done without him,” Roosevelt said after McDuffie provided alcohol rubdowns and hot lemonade when Roosevelt caught cold during his campaign for the vice presidency in 1928.19 McDuffie could be superstitious about his boss’s well-being: following a 1933 assassination attempt on President-elect Roosevelt in Miami, the valet removed the tie FDR was wearing that day from the presidential wardrobe. “No sir, Mr. Roosevelt, this is one tie I won’t let you wear again.”20 He worried over the president’s weight and managed the amount of food he was served when Roosevelt seemed to be putting on a few pounds.21

The president’s appearance was a priority for McDuffie. The first lady would remind her husband that he needed a haircut, but he resisted the ritual until Mac joined the prodding. The president would give in, but Lizzie said he wore an “injured expression” while sitting for a trim.22 Mac cared for the president’s clothes, but it was Roosevelt, who delighted in mundane domestic decisions, who chose his attire for the day, selecting from two or three suits and a rack of ties that the valet laid out for him. (FDR preferred blue and gray suits, white shirts, solid colored ties, and blue and gray socks).23 Knowing that Roosevelt loved a few of his threadbare sweaters, Mac saw to it that they were clean and mended, for the president refused to throw them out and became irritated if something had been discarded without his permission.

McDuffie traveled extensively with Roosevelt who, because of his paralysis, required help outside of a valet’s typical duties. The president depended on Mac to help him in and out of bed and to strap on the steel leg braces he wore. McDuffie helped Roosevelt dress in the morning and lifted the president into his wheelchair before delivering him to his office each day. His job was so vital that when the valet was wrongly detained by Brazilian police during a 1936 visit to Rio de Janeiro and missed the departure of the presidential ship USS Indianapolis, the navy’s USS Chester was held up in order to reconnect the president with his valet. “It was indeed an experience I never want to happen again,” he wrote Lizzie.24

The McDuffies’ relationship with the first family made them celebrities among African Americans, and they used their fame to promote their boss and to keep Roosevelt apprised of issues affecting black people across the country. “My husband and I received many letters from Negroes who heard of our position in the Roosevelt household,” said Lizzie, who brought to the president’s attention stories of discrimination in the postal service, in the Works Progress Administration, and in several legal cases involving black Americans.25 Mac spoke to organizations that promoted black causes and occasionally made news with his affectionate words about Roosevelt. “There’s nothing artificial about Mr. Roosevelt’s smile,” he told the New York Times.26 “FDR Interested in Masses, Says Irvin McDuffie,” proclaimed a headline in the Atlanta World in 1938.27 The Associated Press quoted him saying that Roosevelt was “the kindest and finest man in the world.”28 FDR returned the esteem.

In 1939, McDuffie suffered a nervous breakdown.29 When he was able to work, Roosevelt arranged for a job in the Treasury Department, while Lizzie continued her White House duties until FDR’s death in 1945. They returned to Atlanta, where Mac died the following January on what would have been FDR’s 64th birthday.

John Moaney

President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Valet

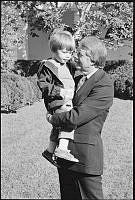

The phrase “No man is a hero to his valet” could not be applied to John Moaney. The Maryland native joined the U.S. Army on the eve of World War II and was assigned to the 751 Quartermaster Company. In August 1942, he was transferred to General Dwight Eisenhower’s personal staff at Telegraph Cottage outside of London during the planning for the invasion of North Africa. As Supreme Commander of Allied Forces, Eisenhower enjoyed the perquisites that accompanied his status as a commanding officer, including a household staff made up of enlisted men who served as butlers, cooks, drivers, and secretaries. As his son, John S. D. Eisenhower said, “He always had a comfortable house."30

Moaney shared a small house on the grounds of Telegraph Cottage with another enlisted man on the general’s staff. Officially, his assignment was to help in the kitchen with the preparation of and serving of meals for the household. Unofficially, he became caretaker to the general’s dogs Telek and Khaki and the twenty-five Scottie pups they produced in various locations. “He named all the pups,” said John Eisenhower.31 Sergeant Moaney was devoted to the general’s dogs. Michael “Mickey” McKeogh, an orderly on the general’s staff, recalled how Moaney tended to one of Khaki’s sick puppies: “He fed it for four days with a medicine dropper. And then it died anyway, and he pretty near cried.”32

It was Moaney who was charged with packing up the household into “footlockers and bags and boxes”33 each time the general relocated as the war progressed. When the end of the war was in sight, most of Eisenhower’s staff was eligible for discharge. All opted to return to civilian life except Moaney. McKeogh remembered that “Moaney had enough points but he didn’t want to get out of the Army—not as long as he could be with the general. He called him ‘General Eisenhouse,’ the way he always did, and said he didn’t want to leave him.” Eisenhower’s regard for Moaney was reciprocated, as Eisenhower “liked to have Moaney around, because he knew his habits.”34 “I just wanted to stay with him,” Moaney said.35

Returning to the United States, Moaney married in 1946 (his first wife and children had been killed in an automobile accident years before), and his wife Delores joined the Eisenhower household as a cook in 1948, moving with the family to Columbia University, where Eisenhower served as president. When Eisenhower was named supreme commander of NATO forces in Europe, Moaney was faced with leaving his wife to accompany Ike to Europe. According to John Eisenhower, the general told Moaney, “Well, I guess this is the end of the line for us. You’ll have to stay here with your young wife.” Moaney replied, “I knowed you before I knowed her.”36

It was Moaney's job to awaken the president in the morning to remind him of the day's schedule.

John Hutton for White House Historical AssociationWith Eisenhower’s election to the presidency in 1952, the Moaneys accompanied the first family to the White House, settling into staff quarters on the Third Floor. Moaney cared for the president’s clothes, which, for most of their time together, had consisted of uniforms. “When he first went up there [to Columbia] he didn’t have but three good suits. He’d wear one one day and one the next day, then he’d start back over again,” Moaney said.37 In addition to caring for the president’s clothes, it was Moaney’s job to awaken the president in the morning, remind him of the day’s schedule, pack the luggage for trips, and prepare the ingredients for Eisenhower to make his homemade vegetable soup. He ran the projector when the Eisenhowers decided to take in a movie, and the two were often seen on the South Lawn Moaney shagging golf balls while Ike practiced his drive. “When in the White House, he was known for insisting that the regular servants there know exactly what ‘duh General’ wanted or needed,” said John Eisenhower. “He was no pushover when it came to Dad’s interests.”38 When the Eisenhowers extended an invitation for the Moaney family to visit the White House in 1957, thirty-two extended members of the family showed up.39

Upon his retirement in 1961, the Eisenhowers settled into their Gettysburg farmhouse, and the Moaneys went with them. The pace of life there slowed: Delores continued her cooking duties while John tended to farm chores and grew close to the Eisenhowers’ grandson David. After Eisenhower’s death in 1969, Moaney served as an honorary pallbearer at the funeral. The couple lived at Gettysburg, tending to Mamie Eisenhower until 1974, when they retired and moved to Washington. John Moaney died the following year. Loyal to his boss until the end, he told Mrs. Eisenhower after Ike’s death, “I ain’t workin for you; I’s takin care of you for the gennul.”40