Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Seances in the Red Room

How Spiritualism Comforted the Nation during and after the Civil War

Death plagues us all: it is the only certainty in life and plays an integral role in the human experience. When a loved one perishes, it is their survivors who are left to pick up the pieces. In a time of mourning, grief-stricken loved ones turn to a plethora of coping mechanisms, and over time the way we mourn has evolved dramatically. Often times, people turn to organized religion or spirituality as a source of comfort and connection to those who were lost. Many White House ghost stories, most of which are centered on the Lincoln family, have roots in the nineteenth century when spiritualism and séances were rather common because the Civil War changed not only how Americans understood death but also how they mourned.

The bloodiest conflict in the nation's history was the American Civil War (1861-1865). Fought over the expansion of slavery, the Civil War resulted in approximately 750,000 American fatalities, nearly equal to the total number of American deaths in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War combined.1 Never before had the nation experienced death like this. It is important that the survivor understands the meaning of their loved one's life and death in order to properly grieve. According to historian Drew Gilpin Faust:

The particular circumstances of the Civil War often inhibited mourning, rendering it difficult, if not impossible, for many bereaved Americans to move through the stages of grief. In an environment where information about deaths was often wrong or entirely unavailable, survivors found themselves both literally and figuratively unable to ‘see clearly what… has been lost.’2

When these soldiers perished far away from home, observance of grief was impossible and the state of the soul of the deceased at the time of death was forever lost to the family. Bodies were left on the battlefield for a variety of reasons: lack of a structured, recovery system, attempts to disgrace the enemy and lower its morale, junctures of battle, and discrimination between officers and their subordinates.3

This photograph, taken by Mathew Brady, shows the south front of the White House during the Lincoln administration (1861-1865).

National Archives and Records AdministrationWhile spiritualism, a belief system centered on a doctrine in which the dead can communicate with the living, existed long before the Civil War, it was not popularized until the mid to late nineteenth century. By 1897, it was believed that spiritualism had more than eight million believers in the United States and Europe, mostly drawn from the middle and upper classes.4 The uniqueness and scope of death during the Civil War left thousands of families without the proper outlets to grieve. It transformed wives into widows, children into orphans, and mothers into mourners. According to one study on the rise of spiritualism during the nineteenth century, “Spiritualist activity increased rapidly in America at a time when bereaved citizens were seeking new assurance of continuity and justice after death and when traditional religion was becoming less able to offer this assurance.”5 For instance, séances were used as an attempt to reach out to lost loved ones with the assistance of a trained medium. This professional claimed the mystic ability to communicate with the deceased.6 Spiritualism expanded so rapidly during and after the Civil War because it offered grieving survivors closure that the war had denied them.

Ordinary Americans were not the only ones to turn to spiritualism as a coping mechanism during the Civil War. In fact, First Lady Mary Lincoln, the wife of President Abraham Lincoln, practiced spiritualism in the White House. Mrs. Lincoln was born into a wealthy, Protestant family from Kentucky in 1818. Throughout her life, she suffered an immense amount of loss including her mother at a young age, three out of four of her children, and the brutal assassination of her husband before her very eyes.7 She first turned to spiritualism as a tool for processing her grief after the death of her second youngest son, William or "Willie", in February 1862. According to a newspaper article published the day after Willie’s death, “His sickness, an intermittent fever assuming a typhoid character, has caused anxiety and alarm to his family and friends for a week past … The President has been by his side much of the time, scarcely taking rest for ten days past.”8 Willie was only eleven years old at the time of his passing, a victim of typhoid fever.

This portrait photograph shows Mary Lincoln as First Lady of the United States (1861-1865).

Library of CongressFirst Lady Mary Lincoln became inconsolable after the passing of Willie and desperately searched for an outlet for her grief. Shortly after his death, she was introduced to the Lauries, a well-known group of mediums that were located in Georgetown. Mrs. Lincoln found such comfort from the séances held by the group that she started hosting her own séances in the Red Room of the White House. There is evidence to suggest that she hosted as many as eight séances in the White House and that her husband was even in attendance for a few of them.9 The séances proved to be such an effective coping mechanism for Mrs. Lincoln that she once remarked to her half-sister that, “Willie Lives. He comes to me every night and stands at the foot of the bed with the same sweet adorable smile that he always has had. He does not always come alone. Little Eddie [her son that perished at the age of four] is sometimes with him.” 10 Through spiritualism, Mrs. Lincoln, like many Americans at the time, found solace in the belief that one could communicate with lost loved ones. Despite this, Mrs. Lincoln did take a step back from her practice after several months due to societal pressures.

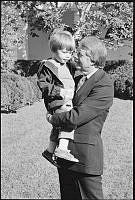

William (Willie) and Thomas (Tad) Lincoln pose with their cousin, Lockwood Todd, the nephew of Mary Lincoln. This photograph was taken in Mathew Brady's Washington, D.C. studio in 1861.

The ghosts of Willie and Eddie Lincoln were not the only Lincoln ghosts believed to haunt the White House. The ghost of their father, President Abraham Lincoln, is arguably the most well-known spirit at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The assassination of President Lincoln shook the nation to its core and almost immediately rumors about his spirit began to circulate. Many cite that he appears in both the Lincoln Bedroom and the Yellow Oval Room. First Lady Grace Coolidge, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands have all claimed to have seen Lincoln's ghost.11 These rumors were perpetrated by White House employee, Jeremiah “Jerry” Smith. He served as the official duster of the White House for over thirty-five years, starting in the late 1860s. He would often congregate around the North Entrance and spin tales of ghost sightings to reporters on slow news days.12

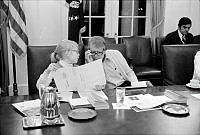

William H. Mumler took this photograph of Mary Lincoln around 1872 in Boston, Massachusetts. Mumler was a spiritual photographer, who claimed that his technique captured not only his subjects but also their departed loved ones.

Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, IndianaIn 1870, Mary Lincoln secretly visited William H. Mumler, a self-proclaimed spirit photographer. Despite the fact that he was accused of fraud, the former first lady requested to be photographed with her late husband. The resulting picture, which depicts the ghost of President Lincoln looking over his wife, was circulated widely, though it was not alone. In fact, “Prints, photographs and literary representations of Lincoln as a spirit abounded in the months and years after his assassination, chronicling his passage into the afterlife from the moment the Angel of Death appeared above his bed.”13 The nation fought so hard to hold on to Lincoln's ghost because he represented the idea of a spirit coming home and looking over its family from above. During a time when so many families had lost fathers and sons, it was comforting to know that the father of the nation was still looking over them as well. Hearing stories of Lincoln’s ghost gave these families hope that their own fallen father figures were also looking over them as well. Moreover, his ghost demonstrated that he and the soldiers who perished in battle were able to find comfort despite the circumstances of their untimely deaths.

This lithograph print, published by Currier & Ives, shows the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865. The president was carried across the street to Petersen House, where he died the following morning.

Library of CongressThe majority of White House ghost stories developed during the nineteenth century when spiritualism reached its peak. This was a side effect of the nation’s shifting conceptions of death and mourning during the Civil War. Today, these stories have lost most of their prevalence due to the fact that death is perceived much differently in the twenty-first century. The level of deaths that occurred during the Civil War no longer holds true in comparison to modern warfare. Fallen soldiers are easier to identify thanks to advancements in DNA and the use of dog tags. Additionally, life expectancy and childhood survival rates have climbed exponentially since the nineteenth century. Death is less commonplace and visible then it was during the Civil War. Spiritualism offered a coping mechanism that was necessary during a time when life was shrouded in death. While today's society looks at the ghost of Lincoln as a silly myth, it once brought solace to a wounded nation.