Rubenstein Center Scholarship

The History of Lafayette Park

Today, Lafayette Park sits just north of the White House, enclosed by H Street NW (north), Madison Place (east), Pennsylvania Avenue (south), and Jackson Place (west). This seven-acre public park is named after the famous French Revolutionary War hero, the Marquis de Lafayette. It has served as a graveyard, construction site, market, public space, and neighborhood throughout its 200-year history. Lafayette Park was depicted in the original plans for Washington, D.C., and has witnessed countless significant events, including the construction of the White House, various protests and demonstrations, as well as celebrations and commemorations.

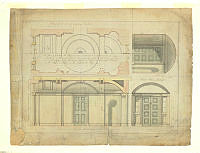

This is a copy of Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's 1791 plan for Washington, D.C. In this version you can see L'Enfant's original plan for a presidential palace features a three-avenue approach, culminating in a semi-circle.

Library of CongressFollowing the passage of the Residence Act in 1790, plans were made for a new capital city along the banks of the Potomac River. In 1791, a group of local landowners agreed to deed their land to the government for the creation of this new capital. According to French-born engineer Pierre (Peter) Charles L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for the capital city, a presidential palace would be constructed featuring a grand ceremonial entrance with three approaching avenues culminating in a “semicircular forecourt.”1 However, this plan never came to fruition, and the plans for a large presidential palace were scrapped in favor of a smaller President’s House. When L’Enfant’s palace plans were abandoned, the three-avenue approach was also eliminated. In response, a local landowner and entrepreneur named Samuel Davidson disputed his deeded land transfer. Davidson had agreed to deed the tract of land, originally part of a plantation called Port Royal, to the government, after purchasing the land from a man named John Pearce, whose family had owned the land for several generations. Davidson believed the land would become part of L’Enfant’s grand ceremonial entrance. After repeated instances of insubordination, L’Enfant was dismissed in February 1792, and his plans were altered.2

A 1794 engraving by surveyor Andrew Ellicott instead depicted the space in front of the White House as an open common, surrounded by city lots to be sold and developed.3 Samuel Davidson balked when he discovered the divergence from the L’Enfant plan because the new plan divided his land into fewer lots, which meant less money from selling the tracts. After raising his grievances with the three commissioners overseeing city construction, they agreed to auction the square in front of the White House as one large block, which Davidson then bought for $5,440 dollars to ensure that no one else could develop the land while he advocated for L’Enfant’s original design.4 Although he had several opportunities to sell the property during the 1790s, none of the sales went through. Davidson was ultimately unsuccessful despite directly petitioning President George Washington and arguing with the commissioners “at this day there is no real fixed plan for the City of Washington.”5 Like other property owners that deeded their land to the federal government in 1791, he was disappointed in his investment and continued to quarrel with the commissioners and President Washington, urging them to follow the L’Enfant design. Ultimately, there are still unanswered questions about Davidson’s ownership and use of the square in front of the White House, and the matter appears not to have been settled until after his death in 1810.6

This map, completed in 1876, depicts land ownership prior to L’Enfant’s survey and the creation of plans for the new capital city. Many of the landowners on this map deeded their land to the federal government in 1791 for the construction of Washington, D.C.

Library of CongressWhile Davidson battled over the future of the land with President Washington and the commissioners, White House construction began with the laying of the cornerstone on October 13, 1792. Work accelerated the following spring, continuing for the next eight years. In 1791, prior to his removal, L’Enfant ordered the excavation of the cellar, carried out by enslaved African Americans. He also built huts in the park to house enslaved workers.7 In 1792, a carpenter’s workshop was built in the middle of the area, near the location of today’s Andrew Jackson equestrian statue. The following year, the commissioners built housing for additional workers. There were about twenty wooden structures housing American, English, Scottish, and Irish wage laborers and craftsmen. Other brick barracks were also built, and Davidson later purchased one of these barracks for $2,000. Some of these buildings housed enslaved African Americans hired out to work on construction by their owners.8 By the fall of 1793, brick mason Jeremiah Kale had been hired to make bricks for the White House using kilns set up in the square.9 In addition to the brickmaking, Samuel Davidson also cleared his property of trees and sold sixty cords of wood to the government to fuel the fires of the brick kilns in the square.10

President John Adams moved into the White House on November 1, 1800. However, construction efforts continued around the house, and the square did not yet look the part of a public park. It lacked plantings or barriers, was constantly muddy, and it was devoid of private homes and residences. At the time, it was commonly known as President’s Square or “the common.” According to recollections by Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, a later resident of the neighborhood, a racetrack was built in the 1790s adjacent to the park between 17th Street and 20th Street. The curve in the track crossed over 20th Street at one end and 17th Street at the other, therefore extending slightly into what is now considered Lafayette Park at the northwest corner.11

After moving into the White House in 1801, President Thomas Jefferson made great strides to improve the White House Grounds. The grounds were littered with construction materials and huts, kilns, pits, and rubbish piles. An 1807 drawing by Jefferson suggests that he wished to install a straight section of wall along the north side of the White House along what is today Pennsylvania Avenue. By 1808, he had completed several stone ha-ha walls to help enclose the White House Grounds and establish some privacy, while still leaving the White House open for events like the Fourth of July. Jefferson regularly participated in public celebrations of the Fourth of July in the President’s Square. A series of tents and stalls were set up and the public enjoyed a “typical country fair” to celebrate the holiday. There were games, dog races, and cockfights. Revelers also enjoyed an array of food and drinks. Political commentator Margaret Bayard Smith wrote of the celebrations:

“At the time there were no buildings or inclosures [sic] in the vicinity of the President’s House, but a wide extended pleasant and grassy common, where the inhabitants found pleasant walks and the herds and flocks abundant pasture...Temporary tents and boothes [sic] were scattered over the surface, for the accommodation of the gay crowds, who here amused themselves and from whence there was a good view of the troops as they marched in front of the President’s House...”12

Despite the slow development of the new Federal City, the common in front of the White House became a crossroads for the early population of Washington, D.C. after an early market was established. President Jefferson was frequently seen around the park as members of the public—white and Black, free and enslaved—interacted and went about their daily business. Records indicate that an enslaved woman named Alethia “Lethe” Tanner sold vegetables in the park with her owner’s permission. On July 16, 1810, Tanner purchased her freedom for $275 with money saved from her vegetable stand.13 The market later moved down Pennsylvania Avenue between 7th and 9th Streets Northwest, and eventually became known as Center Market.14

Benjamin Ogle Tayloe described the undeveloped nature of the park around the turn of the nineteenth century: “As late as the War of 1812, I recollect the entire square from Fifteenth to Seventeenth Street, as a neglected common, entirely denuded of trees.”15 The White House was burned by the British during the War of 1812 on the evening of August 24, 1814. Reconstruction of the White House took place from 1814 to 1817, and in October 1817 President James Monroe moved into the reconstructed President’s House. The square was once again used to support this construction, with enslaved and free workers laboring to rebuild the White House.16 Following White House reconstruction, President Monroe worked to develop President’s Park. In 1818, the government commenced a large-scale project to grade President’s Square. Topsoil was smoothed with dragged logs and boards. Both free and enslaved laborers hired out by the government worked on this project.17

As the grading project commenced, some of the Pearce family graves, still located in the square, were disturbed in the process. A young Washington, D.C. resident named Christian Hines notified the Pearce family. Although “Mr. Pearce” was out of town, a “Mrs. Pearce” instructed Hines to gather any remains and reinter them elsewhere. Hines returned to the site, communicated the family’s wishes with Samuel Harkness, Commissioner of the First Ward, who had a case made to contain the remains. Hines later recollected:

“After the earth had been removed from over the remains, it was ascertained that there was little else to take up but a few bones and a little black dust, besides, I believe, a piece of hair-comb, some plaited hair, &c. After gathering the remains together and putting them into the case, we had them placed in a cart and proceeded to Holmead burying ground where we deposited them.”

Hines later returned to the site with “Mr. Pearce” to show him the location of his family graveyard.18 The grading in the President’s Square and other improvements to the White House Grounds continued until their completion in 1834. Treasury vouchers indicate that although some topsoil was added in the square, a massive amount of dirt was ultimately removed from the square, therefore lowering its position in relationship to the Potomac River. The grading and improvements followed a plan, unfortunately lost to history, but likely developed by Architect of the Capitol Charles Bulfinch. Meanwhile, original White House architect James Hoban worked to replace and improve sections of Jefferson’s North Entrance and stone wall. This included the installation of wrought iron fencing to the north of the White House along today’s Pennsylvania Avenue.19

Grading the square also inspired landscaping improvements. In 1817, President Monroe appointed Charles Bizet “Gardener to the President of the U. States.” Although, Bizet did not complete much landscaping in the President’s Square, it seems that he may have attempted to establish some ground cover. Research by historian Jonathan Pliska notes references to cartloads of manure and orchard grass seed deposited in the square, along with “a note that it took twelve days to hand mow the entire President’s Square with a scythe.”20

As landscaping in the President’s Square developed, so did the President’s Neighborhood. St. John’s Church was designed by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe and completed in 1816 on the north side of the park. In 1818, Latrobe also designed Decatur House for Commodore Stephen Decatur at the northwest corner of the park. At about the same time, construction on the Cutts-Madison House began on the opposite side of the square. According to historian William Seale, by the time Monroe’s time in office ended, “the carriageway in front of Decatur House had been graveled and designated as 16 ½ Street,” while the same area across the square was designated 15 ½ Street—today these streets are known as Jackson Place and Madison Place.21

Pennsylvania Avenue was cut through the square during the second term of the Monroe administration (1817-1825), formally separating the White House Grounds from President’s Square.22 In addition, around 1826 as grading efforts continued, a wooden fence was added to the perimeter of the park. Although, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact year the separation was made, maps indicate that it likely occurred sometime in the early 1820s. An 1820 map does not show a separation between the President’s Square and the White House Grounds. However, an 1828 map does show the separation, indicating that the Pennsylvania Avenue cut through likely occurred between 1822 and 1828. This cut through coincided with the Marquis de Lafayette’s extended visit to the United States from 1824-1825. Grading in the square along with improvements to the fencing and entrances along Pennsylvania Avenue was finally completed by 1834.

The map on the left from 1820 does not show a separation between the White House Grounds and the park. However, the map on the right from 1828 does show a physical separation. This separation indicates that the cut through of Pennsylvania Avenue likely occurred between 1820 and 1828.

Library of CongressA popular myth is that Lafayette Park was named in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette during his visit to the United States from 1824-1825 by either President James Monroe or President John Quincy Adams. However, the designation of the space as “Lafayette Square” did not occur until around 1834. Lafayette died on May 20, 1834, and shortly following his death, Congress appropriated $1,000 to plant trees and repair fencing in “Lafayette Square” on June 30. Maps also started interchanging the names “President’s Square” with “Lafayette Square.” According to research by historian Matthew Costello, by the time of the Civil War, Lafayette Square had become the common name for the neighborhood, and as a true park emerged the Lafayette name applied to both. This was further solidified with the addition of a Lafayette statue in the southeast corner in 1891.23

The next large scale landscaping project occurred in 1851. Renowned landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing was invited to prepare plans for new landscaping in Lafayette Park, the National Mall, and President’s Park. Downing began drafting the plans. However, he tragically drowned during a boating accident on the Hudson River on July 28, 1852. Despite his untimely death, Downing’s layout of Lafayette Park was still largely carried out and “although subsequently altered, may be the most complete example of his work still in existence today.”24

This photograph of the equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson silhouetted against the North Front of the White House was taken by Bruce White for the White House Historical Association on November 14, 2009.

White House Historical AssociationOn January 8, 1853, an equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson was installed and unveiled in the center of Lafayette Park. Several years earlier, following the 1845 death of Jackson, the Jackson Monument Committee planned for a memorial and artist Clark Mills submitted a design which the committee accepted in 1848. Mills established a foundry at 15th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue near the Treasury Building and cast the bronze monument with the help of enslaved artisan, Philip Reid.25 At the same time the Jackson statue was erected, Congress appropriated some $5,100 to enclose Lafayette Park with an iron fence and four gates topped with eagles. This work was completed in 1854. However, the fencing was later removed in 1889 to provide more public access to the park.26

Between 1872 and 1933, the first major landscaping took place in the park under the authority and administration of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, United States Army. Gardeners added ornamental flower beds and decorative palms. Several inventories of the trees and plants in the park were made, including an 1866 inventory by public gardener George H. Brown. During the 1870s, a display of prairie dogs donated to the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds was presented in the park, enclosed with wire and available for public viewing. The first gas lighting and drinking fountains were installed in the park in 1872. In 1890, new drains were installed in the park as older drains were blocked by expanding tree roots. At the same time, the first graded walkways were also added by the Army Corps of Engineers, providing easier access to the government buildings and homes on Lafayette Square.27

In addition to the Jackson statue, four other statues, each representing a European military leader that fought in the American Revolution, were installed around the turn of the twentieth century. The first statue, depicting the Marquis de Lafayette, was designed by sculptors Alexandre Falguière and Antonin Mercié and installed in the southeast corner of the park in 1891, following debate over whether the statue would impact the view of the White House. The second statue in the southwest corner of the park was dedicated on May 24, 1902. The monument honored the Comte de Rochambeau and was designed by sculptor Fernand Hamar. President Theodore Roosevelt spoke at the dedication, noting the warm relationship between France and the United States. A third bronze sculpture by Antoni Popiel celebrated General Tadeusz Koscuiszko of Poland. President William Howard Taft was present for the dedication on May 11, 1910. The final statue was dedicated later that year, on December 7. Designed by Albert Jaegers, it honored Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben of Prussia. President Taft also spoke at this dedication: “We dedicate today the last of the monuments which fill the four corners of this beautiful square and which testify to the gratitude of the American people to those from France, from Poland and from Prussia who aided them in their struggle for national independence.”28

President Theodore Roosevelt in the reviewing stand for a ceremony to unveil the Rochambeau statue in Lafayette Park on May 24, 1902.

Library of CongressIn 1914, a new park lodge was installed on the north side of the park by 16th Street, replacing an earlier structure first built in 1872.29 The original lodge was a combined watchmen’s lodge, restroom, and tool shed. Congress appropriated funds in 1913 for construction of the new lodge. However, Lafayette Square residents protested over the demolition and the War Department held hearings about the future of the lodge. Despite the local outrage, construction continued, and the new lodge was finished on May 15, 1914. Several years later in 1921, the Commission of Fine Arts authorized a five-year plan to remove and transplant some older trees and replace them with new trees. In 1925, administration of the park was transferred to the Director of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital and in 1929 a complete inventory of structures and features in the park was conducted.30 The next major park renovation occurred between 1936 and 1937 and was directed by National Capital Parks and the Works Progress Administration after the National Park Service began managing the park in 1933.31 It included widening pathways and relocating various trees, shrubs, and flowerbeds.

A major act of preservation in the park occurred in 1962. When President John F. Kennedy came to the White House in 1961, he and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy expressed interest in the historic preservation of Lafayette Park and the surrounding townhouses and buildings on the park, often referred to as Lafayette Square. In particular, the Kennedys were concerned with proposals to build several large office buildings on the Square, which would require demolishing many of the existing historic townhomes. Throughout the early nineteenth century, the neighborhood on Lafayette Square had been home to many prominent individuals including Commodore Stephen Decatur, First Lady Dolley Madison, Francis Preston Blair, Henry Clay, John Gadsby, and William Wilson Corcoran. However, during the later nineteenth century and twentieth century, the area immediately surrounding the park became less residential. Following the Civil War, other government buildings and businesses began to appear on the square including the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company, commonly referred to as the Freedmen’s Bank, The State, War, and Navy Building (today known as the Eisenhower Executive Building), and the Lafayette Square Opera House.32 With fewer residents in the neighborhood, the General Services Administration (GSA) put forward a plan to demolish homes and build office buildings.

The Freedman's Bank was founded in 1865 and later moved its headquarters to Lafayette Square. The building cost more than $200,000 to build. Upon completion, new bank president Frederick Douglass described his reaction to the new building, "The whole thing was beautiful...I felt like the Queen of Sheba when she saw the riches of Solomon, that 'half had not been told me.'" Unfortunately, Douglass soon discovered that the bank had been badly mismanaged, and the Panic of 1873 led to the failure of the bank. The building was demolished in 1899 and replaced with the Treasury Annex. The Annex was renamed the Freedman's Bank Building in 2016.

Library of CongressLandscape architect and urban planner John Carl Warnecke worked to solve this problem, presenting the Warnecke Plan which preserved many of the townhomes while enhancing the nineteenth-century character of the park. It also allowed for the addition of new government buildings behind the townhouses.33 Since 1962, the park has been maintained largely in accordance with the original Downing plan and continued landscaping and infrastructure improvements have been made. In 1970, Lafayette Square became a National Historic Landmark District.34

In this photograph from 1917, suffragists march with banners, picketing outside on the sidewalk in front of the White House.

Library of CongressAs the park developed during the twentieth century, it has also served as a place of protest. Since 1917, Americans have demonstrated in Lafayette Park, picketed the White House, and exercised their First Amendment right of peaceful assembly.35 The suffragists were the first to use protest consistently in Lafayette Park as they brought the issue of women’s voting rights directly to President Woodrow Wilson’s doorstep. On January 10, 1917, twelve “Silent Sentinels” began picketing outside the White House in protest of Wilson’s refusal to support women’s suffrage. The suffragist’s picketing strategy continued even as White House policemen began arresting them on charges of obstructing traffic. Threatened by dissension within his own political party, President Wilson relented on women’s suffrage and advocated for it in his final annual address before Congress. On August 26, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified and made part of the Constitution, finally eliminating gender as constraint for voting. The suffragists’ Lafayette Park protests helped provide momentum to the movement by bringing it directly to the White House. Their protest helped serve as a model for future protests in Lafayette Park throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.36

This photograph, taken on January 19, 1968, shows demonstrators staging a protest of the Vietnam War in front of the north fence of the White House. The protesters carry signs including statements such as "No more...Stop the war!" "Eartha Kitt speaks for the women of America", and "Stop the draft." The previous day, singer and actress Eartha Kitt had become the subject of much controversy for her statements against the war during a luncheon at the White House hosted by First Lady Lady Bird Johnson.

Library of CongressSince 1920, many other groups have protested in Lafayette Park. Following World War II, supporters of civil rights and anti-lynching legislation marched in front of the White House. Although unsuccessful at the time, they set the stage for further Civil Rights Movement demonstrations throughout the 1960s. One of the largest civil rights protests in the park occurred in March 1965 in response to Bloody Sunday, when peaceful marchers advocating for voting rights were beaten by law enforcement in Selma, Alabama, as they attempted to march for civil rights. Protestors spent five days and nights picketing the White House before a crowd of 1,500 people gathered for a “Convocation of Concerned Citizens” on March 13, 1965.37

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s additional protests took place in Lafayette Park. A new generation of women protested in support of women’s rights and the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to end gender discrimination. Demonstrators protested the Vietnam War in the park consistently until the war’s conclusion in January 1973. During President Lyndon Johnson’s administration protestors employed chants like: “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” The first family even acknowledged they could hear the chants from inside the walls of the White House.38 Demonstrators also protested in Lafayette Park in favor of LGBTQ+ rights, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s as the HIV/AIDS crisis primarily affected gay men across the country while the federal government did little to acknowledge the severity of the epidemic. 39

Most recently, Lafayette Park has been the site of ongoing protests concerning police brutality and the disproportionate killing of Black men and women by law enforcement. During the summer of 2020, numerous protests took place in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and in protest of the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police several days prior on May 25 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The protests were largely peaceful; however, some fires and vandalism did occur to buildings and property around the square, including St. John’s Church and Decatur House. In addition, some protestors launched projectiles, including water bottles, at police.40 As a result of the summer demonstrations and additional security concerns ahead of the Inauguration of President Joseph R. Biden following the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, the park was closed to the public, with temporary metal fencing adorned with protest posters and flyers including imagery, quotes, and tributes to Black lives that were lost to police violence. The fencing was slowly removed throughout the spring of 2021.

This aerial view of Lafayette Park and the White House was taken by photographer Carol M. Highsmith in 2007.

Library of CongressToday, Lafayette Park is operated and maintained by the National Park Service, which also oversees the White House Grounds and the wider President’s Park (Reservation Number 1). It is an open public space that continues to support peaceful protests as well as visitors to Washington, D.C. On July 28, 2021, the National Park Service and the White House Historical Association added three new wayside markers on the north side of the park, directly opposite of St. John’s Church where Black Lives Matters Plaza meets the park. The waysides tell the story of protest in the park, the construction of the White House by free and enslaved laborers, and the influence of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in preserving the character of the park.