Slavery and Freedom in the White House Collection: The Fight for Emancipation

This exhibit explores the history of slavery and emancipation in the United States through art, furnishings, chinaware, and other objects in the White House. This exhibit was curated by White House Historical Association historian Sarah Fling.

The nineteenth century brought with it the end of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, precipitated in part by rising abolitionist sentiment. Around the turn of the century, countries began to abolish the slave trade, and the United States followed shortly thereafter in 1808. While these limitations made significant progress toward abolition, domestic slavery and slave trading remained legal and thrived in the United States for decades.

The fight for emancipation throughout the antebellum era is evident throughout the White House—particularly in the Lincoln Bedroom, where artifacts and art reflect the legacy of President Abraham Lincoln. But other individuals, including prominent abolitionists, foreign allies, and enslaved and free African Americans furthered this cause, and these efforts can also be revealed through the White House Collection.

The Path to Abolition

While there has always been resistance to slavery, abolitionism as a political and social movement gradually expanded during the first half of the nineteenth century. Religious groups such as the Quakers and organizations like the American Anti-Slavery Society (founded in 1833) mobilized to convince the public that slavery was morally evil, lobbying the federal government to prohibit slavery across the country. These efforts, led by abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, and Sojourner Truth, continued until the abolition of slavery in 1865.

Gallery

Below is a ca. 1824 engraving of James Armistead Lafayette, the enslaved man that served in Marquis de Lafayette's unit and who later obtained his freedom with the help of Marquis de Lafayette himself.

The Road to Civil War

As the nineteenth century unfolded, sectional conflict over the expansion of slavery in the West led to a series of political compromises and violent engagements that drove the country closer to war. Art and objects have the ability to communicate the tensions that gripped the country in the antebellum era, reflecting and shaping the opinions of everyday people.

Gallery

Emancipation Proclamation

While he is known to many today as the “Great Emancipator,” Abraham Lincoln’s views on slavery were more complicated than that title might imply, evolving significantly during the four years of his presidency. Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass were highly critical of Lincoln’s sluggishness toward emancipation, but as time went on, Lincoln worked to end slavery in the United States.

On April 16, 1862, Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, which freed nearly 3,000 enslaved people in the nation’s capital and provided compensation to slave owners. Following the Union Army’s victory at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln took another important step toward emancipation, announcing his intention to free enslaved people in rebel-held territory with a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in his office upstairs at the White House—now the Lincoln Bedroom—granting freedom to enslaved people held in bondage in rebelling Confederate states.

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Courthouse to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, effectively ending the Civil War. However, news of the surrender and emancipation did not reach all parts of the country for several months. In Galveston, Texas, enslaved men, women, and children learned of their freedom on June 19, 1865, over two years since the Emancipation Proclamation. That day, Union troops arrived in the city and delivered the news that the war was over and the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas were free. The day came to be known as Juneteenth and is now celebrated as a federal holiday.

Gallery

Notice the walnut chair in the bottom left corner of Bicknell’s painting below—a perfect depiction of the J. and J. W. Meeks’ cabinet chairs in the White House Collection. Bicknell’s final version of First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln is in the U.S. Senate Collection today.

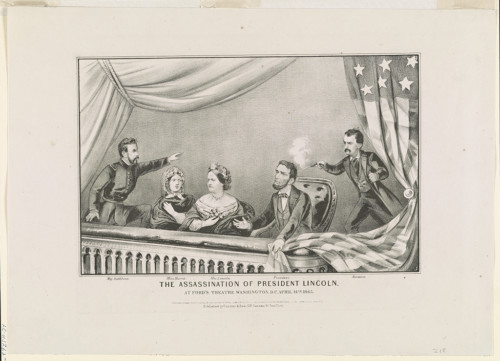

Unfortunately, President Lincoln never saw the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which officially abolished slavery in the United States. He was shot by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865—mere days after the surrender of Robert E. Lee.

Slavery in the United States officially ended with the amendment's ratification on December 6, 1865. The engraving below shows the congressional resolution for the amendment, which proclaimed: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”