Rubenstein Center Scholarship

The Inaugural Address

Origins, Shared Elements, and Elusive Greatness

George Washington established the tradition of the inaugural address on April 30, 1789. After taking the presidential oath of office on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City, he gave a speech inside the Senate chamber before members of Congress and invited dignitaries. Approximately one hundred people heard Washington speak. Many of the formal details, such as the location for the administration of the oath and his speech, were determined by parallel committees in the House of Representatives and the Senate.1

Representative James Madison of Virginia persuaded Washington to give a short speech about governing values and principles rather than a long, detailed lecture elucidating plans for his presidency.2 Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania noted that President Washington, not particularly comfortable with oratory, trembled as he spoke during the twenty-minute address. In addition to his aversion to public speaking, Washington was also likely affected by the enormous grandeur of the moment marking the inception of a constitutional democracy in the United States.3 Indeed, Washington began by admitting that “no greater event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order.”4 Washington’s tempered reluctance and measured ambition are emphasized throughout his first inaugural, perhaps reflective of the doubts entertained by Anti-Federalists that an independent, unitary executive was not compatible with the principles of republican government.

Currier & Ives 1876 lithograph of the first inauguration of George Washington.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Adele S. Colgate, 1962.Since Washington established the tradition of the inaugural address (such practice is not required by the United States Constitution), presidents have used their first speech to speak about the nation’s past, hopes for the future, and their general policy goals for the next four years. While public expectation and tradition dictate some constraints, considerable latitude remains, enabling presidents to adapt the address to their particular speaking style or preferred leadership posture.

Inaugural addresses vary in length, with an average of 2,337 words. William Henry Harrison gave the longest inaugural speech in history at 8,460 words.5 The length of the speech may have cost Harrison his life; he contracted pneumonia soon thereafter and died one month later.

Due to developments in technology and expectations of the president’s public leadership, the method of delivery, its traditions, and immediate audience for the inaugural address has changed over time. In 1797, John Adams reversed the order of the oath and address, giving his speech first and then reciting the oath of office. Thomas Jefferson spoke inside the newly built Senate chamber in the United States Capitol in 1801; his address was subsequently distributed in writing by the National Intelligencer newspaper. In 1817, James Monroe became the first president to take the oath and give his inaugural address outdoors, in front of the Old Brick Capitol. In 1845, James Polk’s inaugural address was transmitted by telegraph, widening the proximate audience. During his second inauguration in 1865, Abraham Lincoln took the oath first and then gave his speech, reversing the previously established order. The first inaugural speech projected by an electronic amplification system was Warren Harding’s address in 1921; Calvin Coolidge’s in 1925 was the first broadcast on radio; and Herbert Hoover’s 1929 inaugural speech was the first recorded on newsreel. Harry Truman received the first televised coverage in 1949. In 1981, Ronald Reagan became the first president to take the oath of office and give his inaugural address on the West Front of the Capitol, facilitating a larger in-person audience. Previously, the East Portico of the Capitol had been used. In 1997, the Bill Clinton gave the first inaugural address broadcast live through the internet.6

Photograph of Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address in 1865.

Library of CongressAlthough the transmission of inaugural addresses and the mode of dissemination have changed over time, it does not necessarily follow that form determines substance.7 In fact, a careful examination indicates that common elements in inaugural addresses persist throughout American history.

Communication scholars Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson treat the inaugural address as its own rhetorical genre. They argue that five key elements establish the inaugural as its own classification of presidential speech.8 Throughout American history, inaugural addresses typically contain the following arguments or attributes:

- Unification of the audience after an election

- Celebration of the nation’s communal values

- Establishment of political principles or policy goals for the president’s term in office

- Demonstration of understanding executive power’s constitutional limits

- Focusing on the present while incorporating elements of the past and future

Thinking about inaugural addresses as a distinct type of rhetoric enables an analysis that focuses on the similarities of speeches over time. Historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. believed that the inaugural address, as a genre of presidential rhetoric, was disadvantaged due to the numerous formulaic constraints placed upon it. He remarked in 1965, “The platitude quotient tends to be high, the rhetoric stately and self-serving, the ritual obsessive, and the surprises few.”9

Despite Schlesinger’s doubts, several inaugural addresses have withstood the test of time and become noteworthy examples of presidential rhetoric. The persistence of common rhetorical elements throughout American history does not negate the fact that certain speeches have distinguished themselves as exemplary.10

John F. Kennedy meets with poet Robert Frost in the White House’s Green Room on Inauguration Day in 1961.

National Archives and Records AdministrationTo determine which are considered the most regarded examples of the genre, I consulted the recent rankings of inaugural addresses from six organizations: U.S. News and World Report, the Council on Foreign Relations, USA Today, the Washington Post, ABC News, and CNN.11 These were the top searched rankings for “best inaugural addresses” online. After compiling a database of all rankings, I determined that there are five inaugural addresses in American history are commonly cited as the most historic, eloquent, and memorable. In chronological order with brief descriptions, they are:

Thomas Jefferson (1801)

In his first inaugural address, Jefferson realized the importance of a peaceful transition of power. After a contested election decided by the House of Representatives, he reached out to his political opponents in his speech, famously stating: “We are all republicans. We are all federalists.” He also established a firm call for unity and reconciliation: “Let us, then, fellow-citizens, unite with one heart and one mind.”

Abraham Lincoln (1865)

Lincoln’s second inaugural address was delivered shortly after the conclusion of the Civil War and less than six weeks before his assassination. Perhaps heralded as the most eloquent inaugural in American history, the speech attempted to examine the war and slavery in a broader context and establish principles for Reconstruction. His concluding sentence is often quoted, although not always in its entirety: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan-- to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933)

In his first inaugural, Roosevelt confronted the paralyzing force of the economic depression engulfing the country by diminishing its power: “So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” He then used a biblical reference (“money changers”) to describe those financiers responsible for money shortages. Then, Roosevelt argued for the aggressive, yet constitutional, use of federal power to ease the blight: “Action in this image and to this end is feasible under the form of government which we have inherited from our ancestors. Our Constitution is so simple and practical that it is possible always to meet extraordinary needs by changes in emphasis and arrangement without loss of essential form.”

John F. Kennedy (1961)

This short, 14-minute speech contains perhaps the most famous sentence in the history of inaugural addresses: “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.” Kennedy’s famous call for public service was one of the few lines in his speech focused on domestic policy. Most of the speech focused on the United States, foreign policy, and the Cold War. He included a number of principles to follow in world affairs, including “Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.”

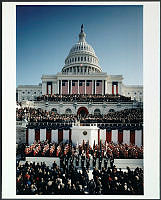

Ronald Reagan (1981)

When Reagan became president, the nation faced an economic slowdown, rising inflation, and high unemployment. Reagan argued that a reduction in size and scope of the federal government was the answer: “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” After acknowledging the challenges ahead, Reagan infused his speech with unbridled optimism. He stated: “Those who say that we are in a time when there are no heroes just don't know where to look.”

The inauguration of Ronald Reagan in 1981, the first inaugural ceremony held on the West Front of the United States Capitol.

Library of CongressWhat do the most memorable inaugural addresses in American history have in common? First, they emphatically signify the end of political division and campaigning in an attempt to foster national unity. Second, they emphasize enduring governing principles instead of specific policy proposals. Third, they underscore the collective nature of ideas rather than focusing on the president in first person as the sole originator of those conceptions (“we” rather than “I”). Lastly, they tend to be shorter, under 2,000 words.12 The abbreviated length may indicate the speech contains a singular theme or focus.13

Inaugural addresses are the first time a new chief executive speaks directly the American people about their vision for the next four years. The purpose of inaugural rhetoric is not to sway public opinion. Instead, the text of inaugural speeches provides an initial blueprint of governance for the electorate. Additionally, inaugural addresses serve as a guidepost for historians, both contemporary and forthcoming, who will subsequently evaluate and contextualize a president’s decisions and leadership. For these reasons, it is no surprise that presidents and their closest advisers spend considerable time and energy crafting these speeches. The gravitas surrounding a presidential inaugural address is a familiar reminder that there is no second chance for a first impression.